How the First Map of D&D's Forgotten Realms Ended Up Above a Pub

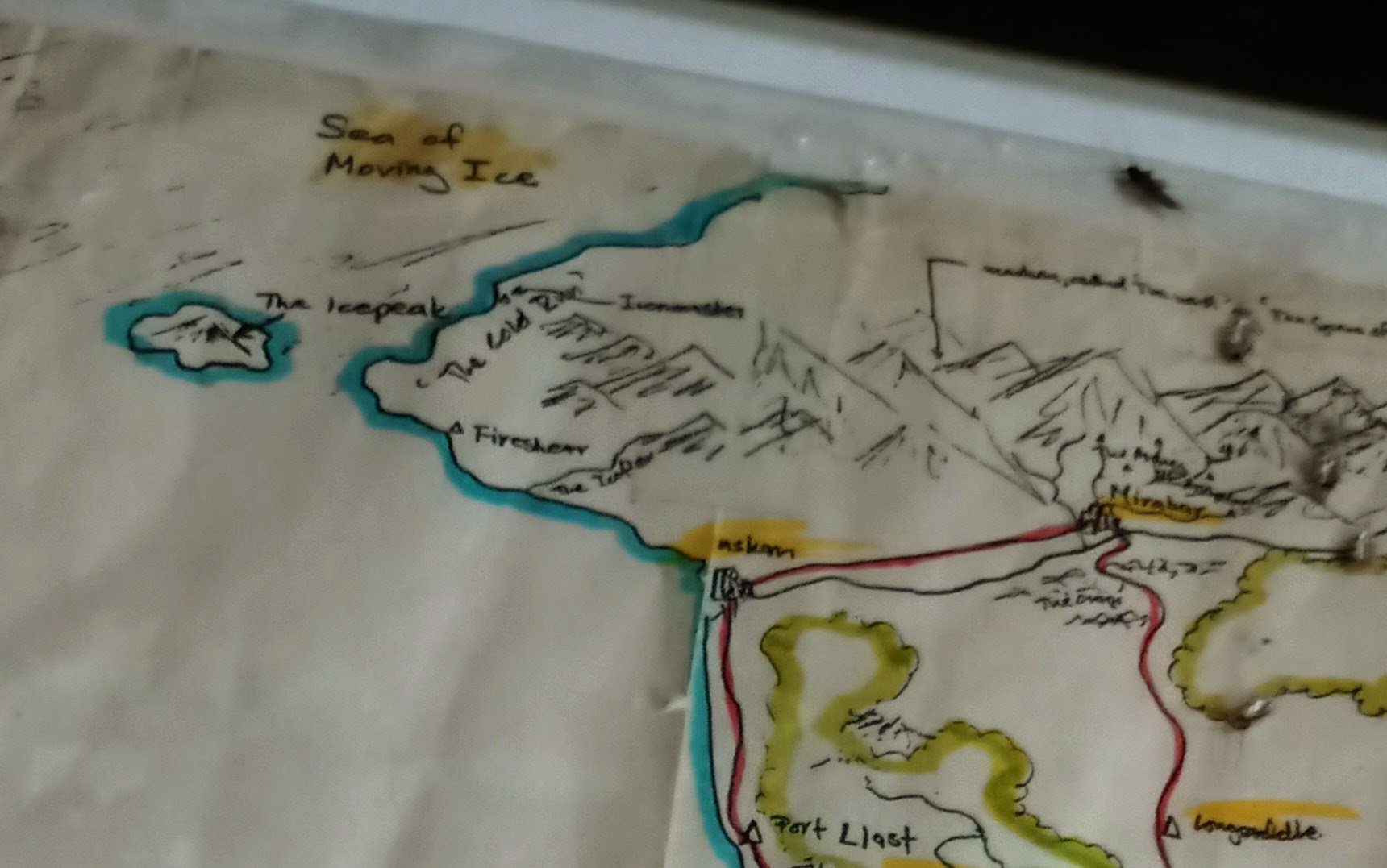

The Sword Coast on the Martin Map.

An artifact from D&D history long thought lost has again been found. Behold the Martin Map of the Forgotten Realms!

I searched for the Martin Map of the Forgotten Realms for years.

My editor pushed me to find it so I include its picture in my book. I heard rumors that it was in Seattle, where it was purchased by a geek bar and used as decoration, but the bar closed years ago and my messages to its Facebook page all went unanswered. Even Realms co-creator Jeff Grubb didn’t know where it was. Like so many precious things from the early days of Dungeons & Dragons, I assumed the Martin Map was lost forever, moldering in some landfill, or buried in a box in corporate storage.

But I was wrong. The map survived, and after a long journey, ended up hanging above a pub outside Madison, Wisconsin in vacuum-sealed, UV-resistant plastic.

How did this irreplaceable artifact of D&D history end up there? And what the hell is the Martin Map anyway?

What is the Martin Map?

The Martin Map is a physical manifestation of a titanic event in geek history, namely the creation of the Forgotten Realms setting for D&D.

In the 1980s, TSR, the first company to publish D&D, was looking for a new setting for the game. And it was Jeff Grubb, who would go on to be known as the architect of the Forgotten Realms, whose next suggestion changed history.

A geyser of creativity that walks in the shape of a man, Jeff Grubb.

Describing the creative force of Jeff Grubb is like describing the ability of a blue whale’s heart to pump blood. (For the record, the blue whale’s heart weighs 400 pounds, and is the size of a refrigerator. It throws 48 gallons of blood with every beat.) The man is a seemingly endless surge of ideas, plots, factions, settings, and scribblings. He has contributed to over 40 different intellectual properties in his decades-long career in writing and design.

And when TSR was looking for a new setting, he remembered Ed Greenwood. Greenwood was a Canadian librarian who’d been writing articles in Dragon magazine since 1979. Greenwood used this framing device where a wizard named Elminster would stop by his home in Ontario, and the articles were often just Elminster’s dictation to Greenwood on some piece of D&D lore. Elminster was from a land called Faerun, and Grubb wondered if Greenwood had more on Faerun, and if he did, would he be willing to sell it to TSR?

Oh yes, Greenwood had more. The Realms predated D&D, and were the setting for a series of short stories Greenwood wrote as he grew up, and then the homebrew setting of his D&D campaign. He kept track of it all on a huge map he kept under his bed. So yes, he had more material, and he would be willing to sell it to TSR. Thus in 1987, Greenwood sold the Realms to TSR for $5,000, and with the sale complete, Greenwood began photocopying his Realms map and mailing it to Jeff Grubb.

The Jungles of Chult on the Martin Map of the Realms.

The map arrived at TSR in pieces. Paranoid about the caprices of the international mail system, Greenwood wrapped each package as though it contained moon rocks or bits of the True Cross. Grubb said, “There were usually several layers of plastic and paper, and the unwrapping usually took about five minutes.” Grubb’s neighbors at TSR would know when a new package arrived from Greenwood because they’d hear the low rustle of cellophane and mild cursing. Slowly, a map the size of a folding table was assembled on the wall outside of Grubb’s cubicle.

Grubb showing a young fan the Martin Map in 1989. Courtesy Anthony Larme.

And then the great work began, the thing that makes the Martin Map a singular cultural artifact: the TSR staff set about changing the geography of the Realms. For example, Greenwood created the Moonshae Isles, which he described as “like the real-world Hebrides, or Ursula K. LeGuin’s Earthsea: a maze of many inhabited rural islands, large and smalls, with shoals and straits in between.” At TSR, the isles became larger and fewer in number and were given to author Doug Niles for a series of novels. These new Moonshae Isles were taped over Greenwood’s originals.

You can see how the TSR folk taped right over Greenwood’s drawings!

And the changes rolled on. Due to a bit of messy handwriting on Greenwood’s photocopies, a “cave mouth” became the Lost Empire of Cavenauth. Glaciers and arctic waste were reduced to make way for Icewind Dale, where a drow named Drizzt Do’Urden first made his appearance. Grubb said, “The major modifications we made early to accommodate other projects, including adopting orphan projects that were not part of Dragonlance or Greyhawk… We gave out chunks of the Realms to computer companies for their development— Neverwinter, Baldur’s Gate, the Moonsea cities, and the Spine of the World to the north.”

The Sword Coast between Neverwinter and Waterdeep.

Grubb tracked the changes on the photocopies hanging outside of his cubicle. He said, “I drew in the coastlines in blue highlighter, the forest outlines in green, and major roads in red. I think we put the major cities in yellow.”

It is these changes that make the Martin Map the unique artifact that it is. Yes, Greenwood has his map of the Realms sleeping beneath his bed in Ontario, but that map is of his Forgotten Realms. The Martin Map, with all the changes and additions and subtractions and misreadings done by the brilliant minds at TSR, is the Forgotten Realms that belongs to us. The Realms as we know it is a fusion of the brilliance of Greenwood, Grubb, and enough fellow geniuses to fill a school bus: Doug Niles, Bob Salvatore, Jim Lowder, Mary Kirchoff, Kate Novak, to say nothing of artists like Keith Parkinson, Brom and Rags Morales. The Martin Map is a foundation of not just games, but novels, comic books, short stories, and soon, a movie.

The map truly is a magic item, one with the power to open the way into another world.

This is the place where Icewind Dale, home of Drizzt Do’Urden should be, but at some point, the alteration fell off, leaving only Greenwood’s original sketch of the north on the Martin Map, instead of the stomping grounds of the famous drow.

Saving History (Or Why It’s Called the Martin Map)

The map might have been lost in 1995 when Jeff Grubb left TSR. He left it hanging on his cubicle wall the day he departed, and it could have ended up in the trash.

But Forgotten Realms editor Julia Martin went up to Grubb’s cubicle the day he left the company. She said, “There was a longstanding tradition of looting the dead, which included things like who gets the chair… That was actually important.”

Martin is a diva of D&D editing. In addition to editing dozens of Realms products over decades, she edited the iconic 3rd edition of the game. She has shepherded millions of words about D&D and its worlds into publication.

And she saw the map hanging on the wall of the now empty cubicle. She saw how Greenwood’s originals had been altered. It was, she said, the only working copy map of the Realms in existence. It was a crucial document for Realms continuity. It was literally irreplaceable.

But the map had meaning beyond that to Martin. It was also a token of her friendship with Ed Greenwood. He was a creative powerhouse and she loved working with him, yes, but there was more between them than just that. She said, “He has a joie de vivre and 1960s sensibility. There is a joyful spirit to him.” And Greenwood was not simply a work acquaintance. He had become her friend, and she said the map, “was a cartographic depiction of both his creativity and our relationship.”

So Martin took the map down off the wall, and “carefully folded it into one of the drawers in my cubicle and made sure it was not being smooshed.”

Surviving Past TSR

In 1997, the map survived another crisis.

TSR spent too much on attempts to expand its business that failed, embarked on a publication strategy that proved disastrous, and borrowed money from its distributor while failing to pay its printer. Things were so bad that the company could not afford to pay the rent on its storage facility, and countless thousands of miniatures, dioramas, and other materials were sent to a Wisconsin landfill. Geek history was left to rust and rot with the garbage.

Then TSR was purchased by Wizards of the Coast, makers of Magic: The Gathering, and Julia Martin saw to it that the map of the Realms drawn by Greenwood and altered by Grubb and company did not end up in a landfill. She took it with her to Seattle when she continued her employment with Wizards of the Coast, and eventually, the map migrated to her closet.

The Martin Map Comes Home

This summer while skimming Facebook, the Martin Map was suddenly there. It was hanging over some guy’s gaming table outside Madison! I was thrilled to see it, but how had it ended up here?

The map abided in Julia Martin’s closet until 2018 when a pet of Martin’s required medical treatment. Veterinary bills piled up, so she contacted an acquaintance who might be interested in purchasing the map: Alex Kammer.

When I asked Kammer how I should describe him in this article, he said, “I’m a freelance writer and director of Gamehole Con.” But that does not accurately sum up the breadth of the man. In addition to being a lawyer endowed with an A+ personality, he is a patron in the classical sense of the word. He uses his financial resources to nourish and protect what he’s passionate about, and in Kammer’s case, that is RPGs. He’s written numerous books with Ed Greenwood, and founded Gamehole Con, a small but vibrant and vital meeting of the D&D tribe that takes place every autumn in Madison, Wisconsin.

He initially started playing D&D with Greyhawk, but found it was dry. The Realms, on the other hand:

“[H]ad a complete cosmology, a complete ecology, and geographical features that actually made sense. There were various nations so it had much more political intrigue. And the materials they published. These wonderful boxed sets! Such delicious detail of all these areas. ”

He is a self-described Realms fanatic, saying, “I adore the Forgotten Realms.”

In the end, Kammer paid $5,000 for the map, as well as notes, plans, and behind-the-scenes documents detailing the birth of countless D&D products. (Coincidentally, it was the same price Greenwood was paid decades before for the entire intellectual property the map had come to represent.)

Eventually, he’d end up mounting it on the ceiling of his game room, which he also calls the Gamehole. He said, “It’s set forever. Hopefully.”

Before mounting it, Kammer set about making sure the Martin Map would last for the ages. He took it to a conservator in Milwaukee, Wisconsin who neutralized the tape that held it together and vacuum-sealed it in UV-resistant plastic. He said he then installed it behind a very thick piece of museum-grade acrylic which was “shockingly expensive.” Such careful preservation isn’t cheap, it turns out, but in the end, Kammer is just “hoping the precautions I’ve taken are adequate.”

How does having history hanging from his ceiling feel to Kammer? He said, “It makes me nervous. [The Gamehole is] located above a pub I own. This is a Civil War-era building, so it’s well-insured, but that’s just money. Fire’s always a concern with a restaurant. I’m hoping the precautions I’ve taken are adequate.”

And so the Martin Map, the embodiment not only of the creation of an epic fantasy world but also a monument to the creatives who forged it, has returned to southern Wisconsin where it was created. It is a reminder of what greatness can result when pen, pencil, and paper meet the infinite capacity of the human imagination.